Many’s story: F.I.G.H.T.ing Refugee Deportation

Many has been fighting his order of deportation for almost 20 years. Many was born in Cambodia in 1976, in the middle of the genocide orchestrated by the Khmer Rouge. Just as the regime was being driven out in 1979, remaining Khmer Rouge soldiers took Many’s family hostage in the jungle for another year before they escaped to the Thai border.

Like so many other refugee families, Many’s family eventually resettled in the U.S. and struggled in neighborhoods plagued by poverty and violence, and schools not equipped to support bright, young, English learner refugee kids like Many.

By the time he was 18 in 1994, Many was convicted of driving a getaway car during a robbery. He took responsibility for his actions and pled guilty, never imagining that in 1996, laws would be passed that would retroactively make his guilty plea a deportable offense.

During his years in prison, Many taught himself immigration law in the prison library and mentored other Khmer and Asian American prisoners. When he was released from prison in 1997, he was immediately detained for two more years in immigration detention. Many fought his detention and joined a Supreme Court case that eventually ruled that indefinite immigrant detention was unconstitutional. He was finally released, but he lives in limbo with a final order of deportation.

Today, Many is a proud husband and father, a dedicated mentor, and a nationally recognized advocate. He has a pardon from the governor of Washington and has been appointed to a statewide commission on prisoner reentry. In 2015, he started a group called F.I.G.H.T. (Formerly Incarcerated Group Healing Together) that brings an Asian American studies-based curriculum and support group to Clallam Bay prison. Through Many’s vision, F.I.G.H.T. aims to support both current and formerly incarcerated Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders through mentoring, advocacy, outreach, and political education.

Learn more about Many’s story.

Learn more about SEARAC’s work to fight mandatory detention and deportation.

Increase Access to Higher Education – Why Are Southeast Asians Not Going to College?

Learn about the challenges that contribute to low college attainment rates of Southeast Asian American students and policy solutions that can increase access to higher education for Southeast Asian American students.

Learn about the challenges that contribute to low college attainment rates of Southeast Asian American students and policy solutions that can increase access to higher education for Southeast Asian American students.

Click here to access.

English Language Learners & Southeast Asian American Communities

Learn about the Southeast Asian American English language learner population, its challenges, and opportunities to raise visibility and provide support for this student population.

Learn about the Southeast Asian American English language learner population, its challenges, and opportunities to raise visibility and provide support for this student population.

Click here to access.

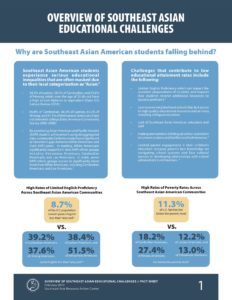

Overview of Southeast Asian Educational Challenges: Why Are Southeast Asian American Students Falling Behind?

Presents the obstacles that keep Southeast Asian American students from reaching their full potential in education achievement, and provides federal and local policy recommendations to remedy these issues.

Presents the obstacles that keep Southeast Asian American students from reaching their full potential in education achievement, and provides federal and local policy recommendations to remedy these issues.

Click here to access.

Moving Beyond the Asian Check Box

This SEARAC policy brief aims to demonstrate national demand for data disaggregation to address the academic achievement gaps that exist within Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander communities.

This SEARAC policy brief aims to demonstrate national demand for data disaggregation to address the academic achievement gaps that exist within Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander communities.

Click here to access.

Data Disaggregation – Opportunities and Challenges

Information in this fact sheet comes primarily from SEARAC’s study of comments submitted to the Department of Education in 2012.

Information in this fact sheet comes primarily from SEARAC’s study of comments submitted to the Department of Education in 2012.

Click here to access.

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) Webinar

Offers an overview of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the need for data disaggregation and targeted supports for English language learners, and strategies for engagement with stakeholders.

Click here to watch the webinar.

Linh’s Story: An American Success Story Made Possible by Family-Based Immigration

In 1986, my dad was forced to flee Vietnam because of persecution. He came to the United States as a refugee and was relocated to Oakland along with my three older brothers. As a child, I remained in Vietnam with my mother and three siblings, and my father filed paperwork to bring the rest of my family to the United States so we could be together again. We spent almost a decade apart before we were reunited as a family in East Oakland eight years later.

Our first Vietnamese New Year together in eight years was one of the most memorable moments of my life. Vietnamese New Year is a time for family reunions and for preparing for the year ahead with your loved ones. We eagerly awaited our red envelopes, we made delicious new years dishes, and I wished a year of good health, prosperity, and longevity to my dad and mom, who I had not seen together in eight years. We were overjoyed when our family grew, and we welcomed my baby sister into the world in Oakland a short time later.

Only in the United States can a son of a refugee receive a world class education and work for top companies, and I am grateful for all these opportunities. I started a management consulting practice business and could not have done so without the unwavering support from my parents and brothers and sisters.

Starting a business is a very personal experience. It is a family experience. I bounced ideas off of my family members, and they helped me to hone in on the right ideas that serve as the foundation for my business. Family members provide you initial funding to launch your ideas and turn them into action. I could not have done it alone. With their support, I have had the opportunity to work with the latest technology innovations and introduce high-value startups to government agencies.

I support the family-based immigration system because it gives families the opportunity to be together and to contribute to this land of opportunity. Without the family-based immigration system, I would not be here, and my family’s support is the foundation from which I have built a successful business.

Learn more about SEARAC’s immigration policy work, and download SEARAC’s family-based immigration fact sheet.

A Mother’s Love: Mee Lor’s Medi-Cal Story

When Mee Lor’s son was born with only one kidney, she was devastated. She worked at Panda Express and didn’t have health insurance. Medical bills were piling up. She recalls, “Everyday I woke up crying because I gave birth to him but couldn’t do anything about his medical bills. I cried every time I looked at the medical bills because I couldn’t afford them. I didn’t even want to take my son into the hospital if it was going to be that expensive.”

When Mee found out she qualified for Medi-Cal, she applied the next day. Her application was expedited, and before long, she had the support she needed to make sure her son stayed healthy. “I felt so relieved after that and didn’t have any suicide thoughts about myself and my son. I didn’t have to worry as much about money and how I was able to support my son.”

When the Republican-controlled Congress began to introduce legislation to repeal the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansion, the federal version of Medi-Cal, Mee knew she had to speak out.

Learn more about SEARAC’s work to protect the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansion.

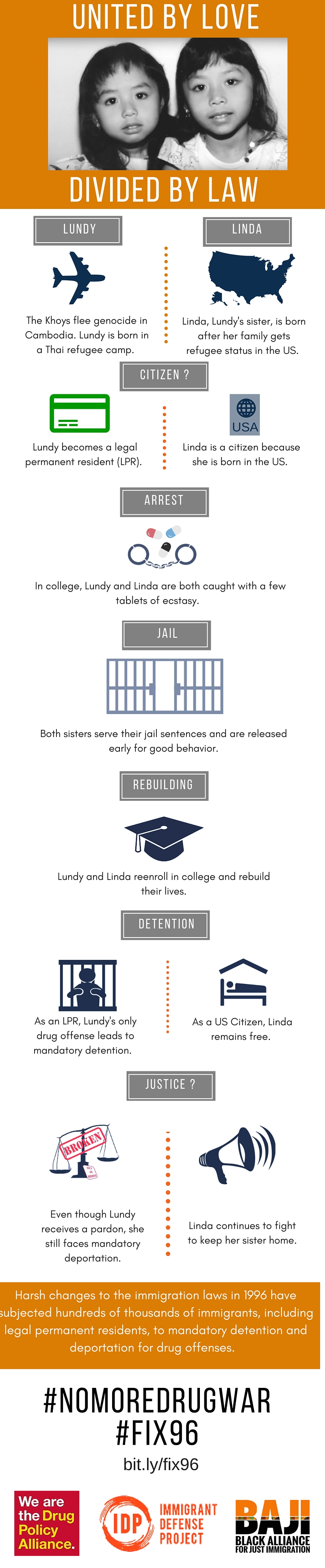

Lundy’s Story: Fighting Deportation to a Country She’s Never Known

Lundy Khoy was born in a Thai refugee camp to Cambodian parents fleeing the war that tore their country apart. When Lundy was a year old, she and her family were resettled as refugees in the U.S.

In 2000 when she was 19, a police officer asked her if she had any drugs. She truthfully told him she had several tabs of ecstasy, which resulted in her arrest for possession with intent to distribute. Under the advice of her lawyer, Lundy pled guilty and was given a 5-year sentence.

Due to good behavior, she was released after 3 months and placed on supervised probation. Lundy went back to school, and began to work to get her life back on track.

Towards the end of her probation period in 2004, Lundy was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers, and informed that she would be deported to Cambodia.

Lundy was incarcerated for almost 9 months during her deportation hearings with no prior warning.

Since Cambodia did not issue the travel documents necessary for deportation, Lundy was finally released. She returned home, finished school, went back to work, actively volunteered in multiple charities in her community, and eventually got married and had a son with her U.S. citizen husband.

After working with a filmmaker to document her story in the short film, “Save Lundy,” she began to advocate in Congress for fair and humane deportation laws. In 2016, she was granted a Governor’s pardon.

In December 2021, Circuit Court Judge William T. Newman Jr. declared Khoy’s plea vacated, lifting the threat of deportation that had hung over her head for more than 20 years. In the months since that ruling, Lundy says that she has felt gratitude and relief, but she has also found herself thinking about all the families that did not have the same resources, whose loved ones were deported before they got a chance to fight.

Learn more

- Watch Save Lundy, a short film about Lundy from 2012 (see below).

- Watch Lundy tell her story on Full Frontal with Samantha Bee (see below).

- Read Lundy’s op-ed in the New York Times, “I am an Immigrant with a Criminal Record.”

- Learn more about Southeast Asian Americans and immigration policy on our website, and learn more about how you can get involved.

- See the infographic below by the Immigrant Defense Project, Drug Policy Alliance, and Black Alliance for Just Immigration comparing Lundy’s circumstances with her sister Linda’s, who was born in the United States.