This article originally appeared on the website of the American Society on Aging.

Editor’s Note: This article represents the third in a series by the Diverse Elders Coalition (DEC) to be published in Generations Today. Articles are connected to ASA-hosted webinars; see end of article to register. The series of articles by the DEC highlights research from The Caregiving Initiative, a multiyear research project funded by The John A. Hartford Foundation.

Challenges facing family members have been exacerbated by the pandemic. While such challenges existed well before COVID-19’s onset, they have come to light in recent months as the global pandemic highlighted disparities in health and aging. For many Southeast Asian American (SEAA) caregivers, these inequities are worsened by language barriers that can lead to increased burden and strain or can trigger intergenerational trauma. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought new hardships for SEAA caregivers such as anti-Asian racism and xenophobia.

Who Are Southeast Asian American Caregivers?

Beginning in 1975, the confluence of the Vietnam War, the Secret Wars in Laos and the Cambodian Genocide forced millions of people to flee their home countries in Southeast Asia. This continues to be the largest refugee diaspora that the United States has seen, with more than 1.1 million refugees resettled from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Today, more than 3 million Southeast Asian Americans call the United States home, populating all 50 states and embodying a rich piece of our nation’s past, present and future.

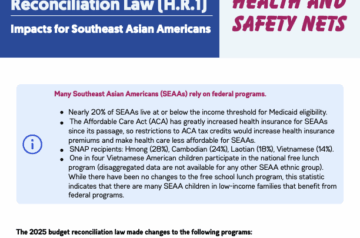

Approximately 98 percent of SEAAs older than age 55 are immigrants or refugees, suffering from some of the highest rates of trauma and depression in the nation (70 percent have been diagnosed with PTSD), and their care largely falls to family and community members.

Culturally and Linguistically Competent Services and Resources

Through the Diverse Elders Coalition (DEC) caregiving initiative, a project aimed at improving the multicultural capacities of healthcare and social service providers, we discovered that there is an urgent need for culturally and linguistically competent services and resources for SEAA caregivers. More than one in four SEAA caregivers in our survey (36.5 percent) reported some or a great deal of difficulty with cultural tasks, such as translating health-related information, overcoming language barriers when talking with providers and legal issues related to immigration or naturalization procedures.

Those who reported some or a great deal of difficulty with cultural tasks were more likely to have elevated levels of four types of strain and depression. Although more research is needed to determine causality, it is clear that there are negative health outcomes associated with cultural task difficulties, emphasizing the importance of culturally and linguistically competent services and resources.

In addition to these cultural task difficulties, in a yet-to-be-published DEC analysis, more than 60 percent of SEAA caregivers reported some or a great deal of difficulty with healthcare tasks such as managing medications or caring for wounds and coordinating or arranging for care or services from healthcare providers, nurses and other service providers.

SEAA caregivers in our focus groups reported needing more information about programs that could help them, from instructions on how to administer medications to how to access financial support. Such programs exist, but instructions on how to access them are rarely translated into SEAA languages (e.g., Hmong, Khmer, Lao, Mien and/or Vietnamese). Additionally, rates of limited-English proficiency are as high as 95 percent among SEAA older adults and 55 percent among all SEAA adults, leaving older adults and caregivers vulnerable to scams, increased fear, misinformation and disinformation.

Navigating the Legal System around Citizenship/Naturalization, Detention and Deportation

“Responsibility of becoming a caregiver for an ill family member can be shared; however, this responsibility usually ends up [with] those who speak the most English,” said one Cambodian caregiver in a focus group. This need for greater assistance to navigate complicated systems, such as the U.S. immigration system, is seen in our survey results as well as in regular inquiries received by the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center (SEARAC).

More than a quarter (28.4 percent) of surveyed SEAA caregivers reported having difficulty with healthcare, legal and financial tasks. Additionally, hostile immigration policies and increases in SEAA detentions and deportations have resulted in adult caregivers being removed from their families and their communities, such as An Nguyen, who cares for his elderly mother. Access to the few supportive, linguistically competent services that exist is limited, and greater outreach, resources development and language access is needed to support SEAA caregivers through these complex systems.

How Has COVID-19 Impacted SEAA Caregiving?

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many in-person resources that elders and caregivers relied upon have become unavailable. Additionally, the transition to virtual services is challenging for older adults and caregivers who speak limited English, who may not write or read in their native languages and who have limited access to technology. Support groups for caregivers, direct services and basic daily activities such as buying groceries or picking up medications all look different than they did prior to COVID-19.

SEARAC’s partners report that they have spent significant time fighting misinformation and disinformation throughout the pandemic, such as a rumor that COVID-19 was transmitted through electronic devices. Basic information such as how to properly wear a mask, the importance of hand-washing, how COVID-19 is transmitted and why social distancing is critical is rarely translated into SEAA languages. A bitter and brutal side effect of COVID-19 has been the uptick in Anti-Asian abuse and harassment that stemmed from our leaders’ insistence upon calling COVID-19 “the China virus.” This may exacerbate existing health disparities among SEAA caregivers.

Best Practices

To meet the needs of SEAA caregivers, service providers must develop culturally and linguistically competent services and resources such as in-language programs and information. Service providers must also acknowledge and support existing programs that effectively address caregiver needs. Below are some best practices outlined in our cultural competency training curriculum that may help service providers to better serve SEAA caregivers:

- Assess for difficulty with cultural tasks in caregiver and patient screening;

- Develop translated, culturally competent in-office materials for disease knowledge, treatments, outreach and training;

- Create partnerships and foster funding to community-based organizations that provide services to SEAA communities;

- Understand that high levels of trauma, PTSD and depression disproportionately impact SEAA refugees, resulting in family involved care;

- Provide culturally competent referrals and resources to resolve high difficulty with cultural tasks.

For more guidance, support and resources to address SEAA caregivers and older adults, visit the Diverse Elders Coalition website at www.diverseelders.org/caregiving.

To attend DEC trainings on the needs of diverse caregivers, register for the March 18 Webinar: Caring for Those Who Care: Meeting the Needs of American Indian and Alaska Native Caregivers.

Sina Sam is the partnership manager at SEARAC in Pullman, Wa. Jenna McDavid is a communications consultant at SEARAC, and Ocean Le, MS, is a program coordinator at the Diverse Elders Coalition, both in New York City.