In “The Forgotten Minorities of Higher Education” published March 18, conservative strategist Ed Blum, who is leading a charge to end affirmative action at Harvard, wonders “Do we want to elevate our race and our ethnicity to the most existential part of who we are?” In other words, if students cannot separate their race from their identities, he argues, the country is “at a very bad gateway.”

Only in a world where historical and structural inequalities no longer dictate who gets resources should race and ethnicity not be considered. But this utopia does not exist. In reality, only 14% of Laotian, 17% of Hmong and Cambodian, and 27% of Vietnamese Americans have a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared with 54% of Asian Americans overall.

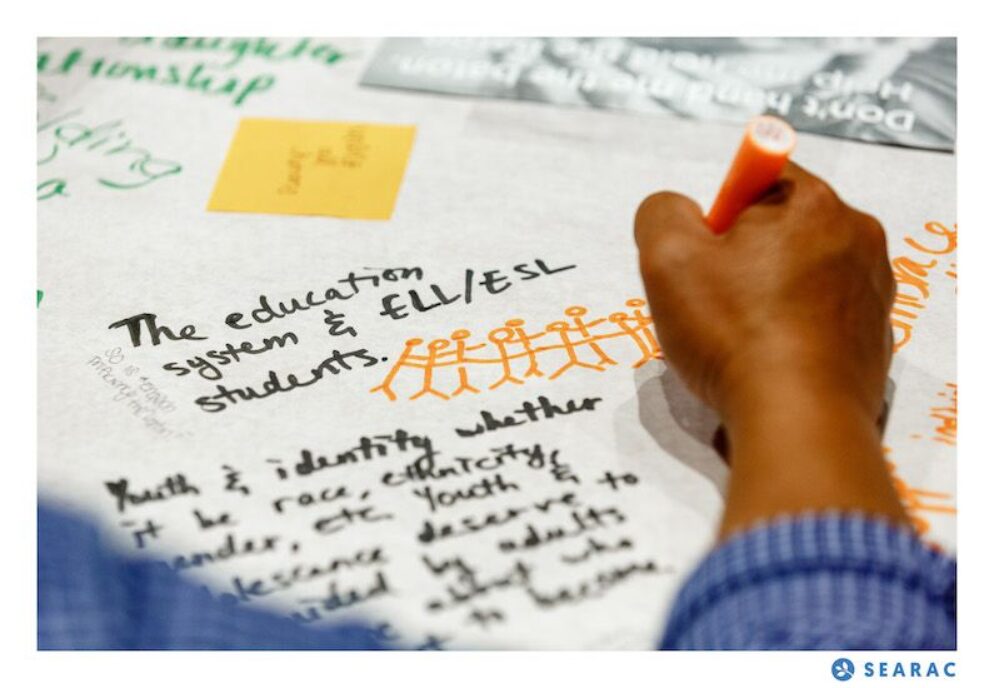

Blum’s rhetorical question dismisses the barriers Southeast Asian American communities have had to overcome as part of their experiences as the children of refugees. Contrary to the myth of the model Asian minority, Southeast Asian Americans face numerous obstacles to college access, such as high rates of poverty, limited English proficiency, and underresourced schools. At the same time, our students’ experiences–and their resilience and perseverance–that are associated with their racial, ethnic, and historical backgrounds are formative and central to their sense of identity. Our students’ self-determination in the face of structural challenges cannot and should not be erased.