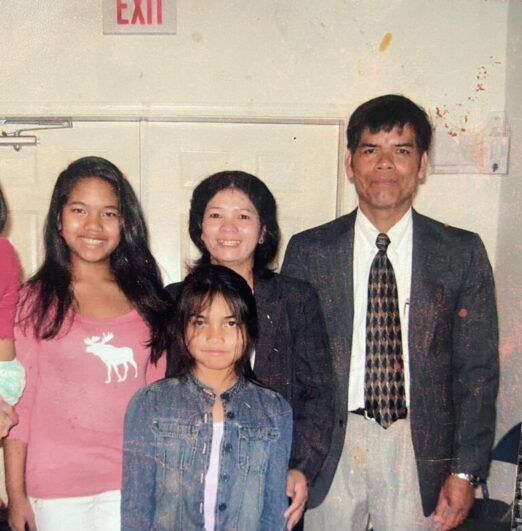

By Phun H

My older sister and I stand at the entrance to the sanctuary, the harmonious singing of the congregation beckoning us in.

Sun scans the backs of heads for mom while I pull and tug at my skirt to ensure it is modest enough for mom’s eyes — although we both know she’ll find a way to remind me that it is not. She spots mẹ’s familiar wavy onyx colored bob among the pews.

We walk toward her, a subtle bow in our posture as we pass congregants. The service began 30 minutes ago, and we have just come in time for the offering. We sit on opposite sides of mẹ, and without taking her eyes from the hymnal, she slips me a bill for offering. The ushers make their way through the pews collecting the money into a gold tray. My dad’s tray is already overfilled with dollar bills. When mboapproaches our pew, he gives me and Sun a slight smile as he takes away the money.

Mẹ points her finger to the place in the hymn and I half-sing, half-mumble in my Bunong. At the final song verse, the church rises together, enveloping me in a sea of adults who have been a part of my childhood — the family friends that have celebrated each birthday and milestone of my life alongside my family. With closed eyes, we stay standing as one of the ushers sends a prayer of thanks to God for the abundance bestowed upon the church, his voice loud but humble.

The congregation sits in unison as the pastor ascends the pulpit to deliver the sermon. Determined, I tell myself that today I will listen thoughtfully to practice my Bunong. However, as the pastor’s words begin to flow, my mind starts to drift away, carried to the landscapes of my family’s village nestled in the central highlands of Vietnam. In front of me, rows of houses and a single dirt path that leads to the church. I begin to deconstruct the village as I know it and imagine the longhouse of my ancestors, filled with the pattering of feet and the hum of conversation. Outside, untamed nature blankets the dirt path, thriving freely. I’m consumed by thoughts of my ancestors’ worship rituals. What did their songs of praise sound like? How did they find solace in their lives? How did they seek guidance from their Gods?

My people, along with other Montagnard people, the ethnic and Indigenous tribes of the central highlands of Vietnam, were evangelized by French and American missionaries. These missionaries learned our language, transcribed bibles, and composed hymns in our tongue. The only Bunong texts, traditions, and rituals that exist are the ones from the church. Mẹ and mbo tell me that Bunong people used to practice animism, but the specifics of traditional Bunong spirituality are known only to a few elders who fought against the forces of colonization, evangelism, and globalization, safeguarding this invaluable wisdom. Most of us in the diaspora do not know.

At times, my identity as a Bunong person can feel indiscernible from my identity as a descendent of colonized peoples. I wonder what defines me as Bunong when my people’s rituals, traditions, and customs have faded over time.

It is hard to extrapolate, and it is a question with which I struggle. A semblance of clarity emerges when my siblings and I gather for dinner together and mẹ and mbo tell us stories of their childhood and youth in Vietnam. My siblings and I listen intently as we savor each spoonful of biap nse, a stew made from ground rice, bamboo, and nse leaves.

Mẹ taps my shoulder, and I return to Sunday service. It is time for the final prayer of the church and once again, we all rise together. The whole congregation prays out loud, sending their gratitude, fears, and reflections to the heavens and their united voices beckon me.

With closed eyes, I direct my words towards my ancestors and send them my gratitude, my fears, and my reflections.

Phun H is SEARAC’s Communications Associate and can be reached at phun@searac.org.

For more blogs in our #VisibleandVibrant series for AANHPI Heritage Month, see:

- “Sharing joy and tradition as kon Khmer” by Nary Rath

- “I remember Hmong means free” by Kham Moua

- “Family-style meals and a community centered movement” by Jazmin Garrett

- “Dual identity” by Katrina Dizon Mariategue

- “Finding home through community” by Lisa Le