By Christine Phan

It’s yet another hot and humid September day in DC, and I’ve made a classic rookie mistake for my first autumn in the nation’s capital — I only brought sweaters. Here I am, sweating in long pants and a button-down and desperately trying to make a good impression on my first day in the office. ‘Business casual’ is a farce.

Standing as close as I can to the coolest ventilator of the office, I pull up my notes for an upcoming phone call, drinking water and gathering my nerves to officially “represent SEARAC” externally. I dial the number and stop short. I look at the area code, squint at it, wondering if it’s real as I wait for the ringtone and click.

“Hello?” the voice says.

“H-hi,” I stutter, “this is Chris Phan from SEARAC, and this is the Southeast Asian American — I mean, from the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center.”

Silence on the other end.

I take a deep breath. “Sorry, I have to ask. Your area code?”

“253.” He confirms. “I’m from Tacoma. And you ….?”

I laugh. “253 here, too.”

One of the very first assignments that I had at SEARAC was to interview community members about their experience in refugee camps and resettling to the United States. These were decades-old stories, and many of these people were kids or teenagers when they first arrived. So their stories are scattered, and when they tell them to me, they piece together anecdotes from their parents or siblings or friends they might’ve made along the journey to their home now.

“I was too young, but my brother reminded me that — ”

“ … I met up with that friend years later in the US …”

“My mom would always tell me the story of how I fell asleep on the boat …”

“It was my first time on an airplane!”

I didn’t really expect my hometown to factor into the mix — growing up, I hadn’t paid much attention to its history. But on this second phone interview, I discovered that Tacoma, a city 10 minutes away from where I grew up, was home to a major Vietnamese and Cambodian community, dating back to the first footsteps of the Southeast Asian American community in the United States. Silong Chhun, a 1.5 generation Cambodian American, outlined for me how the Tacoma Community House, the first organization in Tacoma to help refugee families, was critical to his own family’s resettlement process. So after the phone call, I looked up Tacoma Community House. It was, and has always been, a 10-minute drive from my dad’s medical practice, which served predominantly Vietnamese Americans. It is an eight-minute drive from my old friend’s high school. The importance of this community is just part of a long list of things I didn’t know how to pay attention to growing up.

Throughout my time with SEARAC, I’ve been finding odd, stray threads of commonality. I first heard about the organization through a program it hosts, LAT (Leadership and Advocacy Training) which brings community members to DC to speak and advocate to congressional representatives on behalf of the Southeast Asian American community. Despite being two steps away from Tacoma, I grew up in a predominantly white, affluent community. Like many others, I got a passing acknowledgement of the Vietnamese community in a paragraph in a history textbook, which is more than much of the Southeast Asian American community even receives. So I don’t think you can undercut the significance of the feeling of LAT — of walking through the halls of Congress, into a meeting, and telling your representative that I’m here, that I, and my experiences, and my community, and everything in between, matter.

I flew over right after graduation, unsure of what I wanted to do next and jet-lagged and exhausted from the last year. But it turns out that one of the other attendee’s grandfather was my dad’s patient. Someone shares, “… and I didn’t even see the word Lao mentioned once, in any school history book, growing up” — and I see a whole table nod in recognition. We talk about culturally responsive healthcare, and I think about how important it is that my mom is a medical translator. One woman, it turns out, spent time at the same Malaysian refugee camp as my dad in the ’80s. Albeit by a few years difference, but it was still a thread. Someone else grew up in Torrance, which is where most of my extended family still lives. The two of us discussed some favorite food places, recommendations for Disneyland Fast Pass strategies, and optimal beach weather. Nothing major, but suddenly, Capitol Hill didn’t seem so scary when I was heading in with friends.

“Threads repeated in different places, different names, different years — these are the stories in which I’m finding home.”

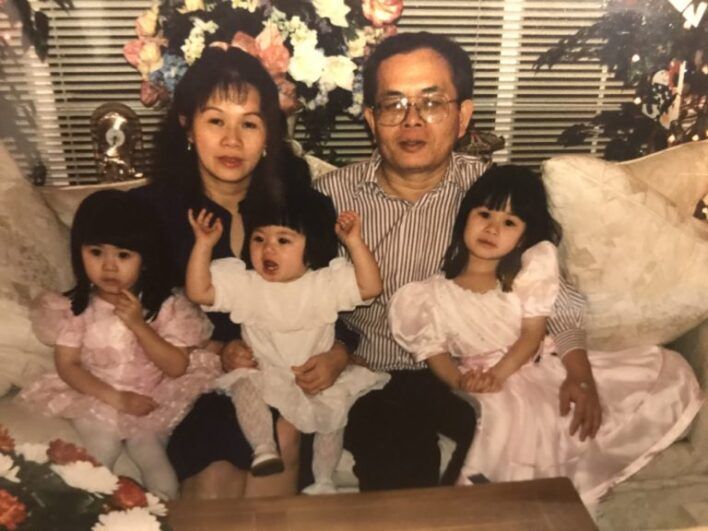

These stories resonate. They, by themselves, are a homecoming of sorts. Little maps of familiarity start popping up across the United States, in worlds that used to be unrecognizable to me. When my mother would tell me stories as a kid, she blended Vietnamese myths in with stories of how she came to the United States. The story of her first chemistry class in community college, the story of my dad’s first job as a pizza delivery man. He would drop off pizzas tucked under his arm, the doughy bread and pepperoni slices piling at the bottom of the box. She would tell me the story of how she chose each of her daughters’ names—- American and Vietnamese. So when I sat around a table at LAT and listened to their stories, I found similar threads. Threads repeated in different places, different names, different years — these are the stories in which I’m finding home.

“You grew up in Washington? So … here?” I get asked, my second month in DC. I correct them — no, Washington State. With pine trees for as far as you can see, with mountains on the east and oceans on the west. I remember deciding, as I left for college, driving down the highway to the airport, that this would always be home. No other place could possibly be home.

And yet, bit by bit, year by year, I find home in other ways. I found it at my college’s Asian American community center, in between student meetings and sleepy golden-hour boba drive-bys. I find home in late night, last minute San Jose food runs after dance practice, or Northern Virginia’s Vietnamese plaza, Eden Center, when my dad told me that when he was in Philadelphia in the 1980s, he would drive three hours just to have some bún bò huế. I find it in our community partners after a long phone call, and after staring at the shape of data that begins to slowly form a story that looks like mine. I find it when, while typing up an interview from SEARAC’s first SEAA ED Dr. Khoa, I realize that he was the vice president of the University of Saigon at the time my dad attended. I find it in our team members, who patiently answered my 75 questions about all the gaps that I’m still trying to understand. I even find home at SEARAC’s Equity Summit, oddly enough. KaYing and Doua, prior executive directors, sit on a panel and say, “We both started out as interns.” A few feet away, fellow SEARAC intern Gina and I look at each other knowingly and whisper mid-panel, “I’ll fight you for that spot.”

Here are the homes we have etched out, year after year, generation after generation. For me, having the opportunity to work alongside SEARAC just means that I’ve gotten what it means to connect, to see, to recognize all the ways the Southeast Asian American community has made homes far, far before I ever came to DC this one ridiculously sweaty, humid fall. From the first time winter hit in Minnesota for the first Hmong-resettled refugees to Vietnamese fishermen recognizing the ports of New Orleans, from the historic establishment of mutual assistance associations (MAAs) to today’s fight against the 1996 laws that reinforce the prison to deportation pipeline, I’m just part of a long legacy of people who continue to build a place to call home.

Born and raised in University Place, WA, Christine Phan is a recent graduate of Stanford University, with a B.S. in computer science and minor in urban studies.