The histories of Southeast Asian refugees have almost completely been erased and rewritten by people who don’t look like us and have never experienced our tribulations. During the mid and late 1970s, Southeast Asians suffered through genocide and war, and we witnessed the unnecessary death of millions by execution, preventable disease, and mass starvation. After having triumphed over these traumatic experiences, Southeast Asians fled their countries and sought safety in refugee camps. These overcrowded camps lacked basic necessities, such as food, water, and housing. Physical and sexual assault were commonplace, furthering the trauma inflicted on our people.

Throughout the 1980s, Southeast Asian refugees became the largest population to ever be resettled at once in the history of the United States. However, the suffering of our communities did not end: Southeast Asians endured continued hardships and oppression as US policymakers scattered our people in order to force their assimilation. We were placed into areas with high poverty rates, without adequate access to resources, and lacking supportive communities. Southeast Asians found it difficult to integrate with little access to linguistically or culturally appropriate support — a problem which continues today. This history shapes the narratives of Southeast Asian Americans now facing deportation. At the height of the “tough on crime” era and the “war on drugs,” the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA) and Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA) were enacted. These two laws dramatically changed the criminal legal system and radically altered the US immigration system, resulting in today’s draconian immigration enforcement system. The system expanded the criminalization of immigrants who are then funneled into the detention and deportation pipeline.

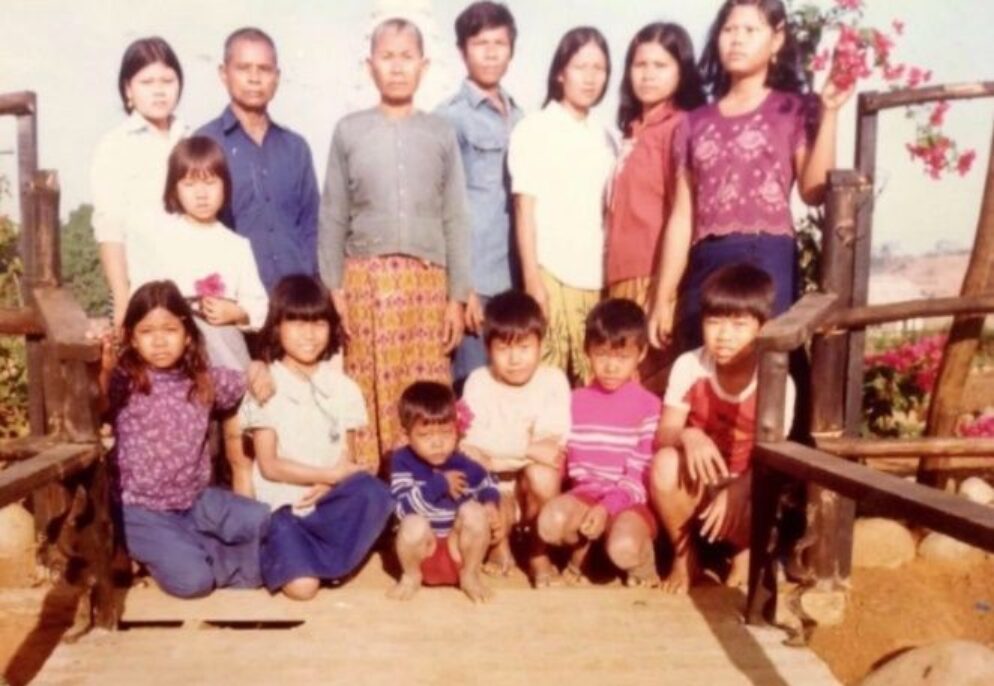

My cousin, Pheap, is among the many Southeast Asian refugees who are facing a life sentence of separation from his family due to the unjust and inhumane criminal legal and immmigration system. Pheap arrived in the US as a refugee when he was a toddler and was granted legal permanent residency status. His father died in the Khao-I-Dang refugee camp, and his widowed mother worked multiple jobs in order to raise him and his two siblings in a society that was not designed for them to flourish. My cousin grew up in poverty, only wore clothing donated to him by local charities, and faced racism and bullying in school. In 2007, Pheap made a mistake and got into a fight; he was arrested and was given misguided legal advice to take a guilty plea, which led him to being convicted of 2nd degree assault. He did not know at the time that accepting the plea deal would mean automatic deportation because of his contact with the criminal legal system. Eleven years later, Pheap was deported to Cambodia for his past conviction — a country he has no memory of — and is unable to ever reunite with our family in the US because no pathway currently exists for those deported to return.

Stories like Pheap’s are not uncommon. Many Southeast Asian American immigrants and refugees have endured severe poverty, facing discriminatory policies and inequitably applied laws that leave us few available avenues for economic or social mobility. Those who became entangled in the US criminal justice system are harshly punished through those laws created during the “tough on crime” era. This is why our country needs a new vision for our immigration system. Earlier this week, Reps. Jesus “Chuy” Garcia, Pramila Jayapal, Karen Bass, and Ayanna Pressley reintroduced the New Way Forward Act because they understand that we must begin to uproot the laws and system that have criminalized our people and torn our families apart. The bill would protect due process protections for immigrants and refugees facing detention and deportation; decriminalize migration; restore judicial discretion for immigration judges; create a five-year statute of limitations for deportability; and create an opportunity for our deported loved ones to come home. As we look to eliminate mass incarceration and create a racially just society, supporting the New Way Forward Act is an essential step toward justice and equity for immigrant and refugee communities.

Nary Rath is SEARAC’s Immigration Policy Advocate. You can contact her at nary@searac.org.

Photo at top: Nary’s family in Khao-I-Dang refugee camp (courtesy of Nary Rath).