My kids have been back in school for about a month. They are fortunate to attend a well-resourced academic institution that had the budget to hire more teachers, separate students into smaller cohorts, adjust classrooms with protective barriers, overhaul its ventilation system, install hand sanitizing stations, and build outside tents to accommodate social distancing. Like many of the parents with whom I’ve spoken, I’m not definitively convinced I made the right decision to remove them from the family bubble we created back in the spring when the COVID outbreak started. And this small worry grew into an enormous cloud over my head two weeks ago when my daughter came home from school with a fever and cough. But after testing negative for COVID and spending the rest of the week recovering at home from an ear infection, we sent her back to school, with the Worry Cloud much smaller than my giant relief of not having to balance work, distance learning, and childcare.

That juggling act back in the spring was precarious. My family was safe, and we had the blessing of security, but my mental health was deteriorating. “You and your kids are resilient,” well-meaning observers would say. “You’re doing a great job managing everything, and you will all get through this.” But as a wise colleague once brought up, that’s the thing about resilience—it always comes with struggle, with grief, with exhaustion, with a feeling like you can’t possibly keep this up any further, but then you do because you have to, because you have people depending on you.

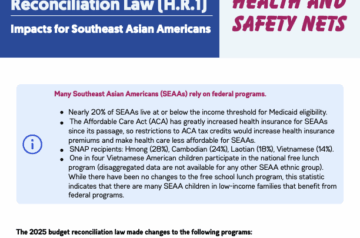

My experience pales in comparison to the stories of severe hardship and anguish this past year that our partners have shared with me and the SEARAC team. In conversation after conversation, Southeast Asian American leaders described communities who were already in desperate need of government leadership now in even more grave circumstances. Many of the families they served were trying to figure out their next meal, let alone how to operate their child’s Google Classroom in a language they didn’t understand. These community advocates also told me about Southeast Asian Americans coming together to donate food, resources, services, and time in the absence of a robust federal response. Because that’s another thing about resilience: achieving it often happens in shared community, with people helping other people.

At SEARAC, we celebrate the resilience of the Southeast Asian American (SEAA) refugee community while at the same time demand changes to the policies that forced community members to become resilient in the first place. We need Congress to step up and prioritize passing a legislative package that addresses the dire conditions SEAA and other communities have faced and are continuing to face. The diverse communities that make America great have the right to thrive, to enjoy a life apart from the adversity and trauma they continuously overcome. Because that’s one last thing about resilience—you’re resilient until you no longer have the energy to be.

Elaine Sanchez Wilson is SEARAC’s Director of Communications and Development and can be reached at elaine@searac.org.