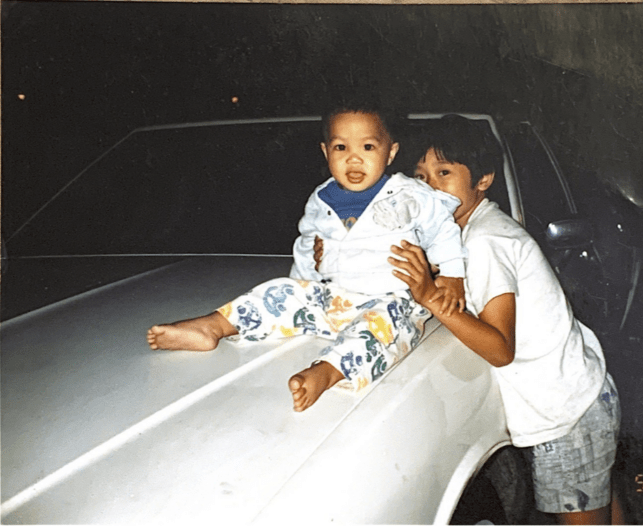

Ocean Le, program coordinator at Diverse Elders Coalition and a SEARAC LAT alumnus, says he’s been his parents’ translator for as long as he can remember.

“I can tell you their Social Security numbers right now because I’ve been supporting them my whole life,” shares Ocean, the eldest of three children to a Nigerian Vietnamese immigrant mother and Vietnamese French immigrant father.

With his dad being a self-employed taxi driver who cannot speak English very well, Ocean has done his taxes since childhood. When he was 8 years old, Ocean would help Vietnamese immigrants move into his Section 8 housing complex in the Kalihi section of his hometown of Honolulu, interpreting for them and communicating their dialogue to the landlord.

As an adult, Ocean continues to serve an essential role as his parents’ translator, educating them on COVID-19 and how his father’s recent diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes puts him at elevated risk of a more severe outcome. Misinformation about COVID is rampant within the Southeast Asian American community, especially among older generations on the Internet, and Ocean is able to fight back by using his health literacy to serve the role of a trusted messenger. “If you have a community where misinformation is thoroughly spread out, but COVID-19 affects that community disproportionately, that’s a recipe for disaster,” he said.

To address these things during this time, you got to make sacrifices, especially if your family is suffering from this, and you come from a low-income Section 8 environment.”

However, English-to-Vietnamese translations can be challenging, Ocean points out. “There’s no word for virus, so you have to use ‘bacteria,” he says. “I have to use examples to point out severity. You might hear, ‘Well, it’s a 3% death rate.’ I have to use an example like, ‘If I gave you 100 Skittles and told you three of those Skittles can kill you, would you still eat those 100 Skittles?’”

The fear of his father getting seriously ill is a constant these days, Ocean says. The booming tourism industry in Hawaii has put food on the table for the families of taxi drivers like Ocean’s father. Ocean says he can’t remember seeing his father in the mornings as a child; he’d only see him at 10 pm at night at the end of a long day of shuffling tourists around the island. In Honolulu, taxis are important, and money was good — until COVID-19 hit. “With COVID, that’s gone now. But he’s not gone. He’s still out there, and he’s putting his life at risk,” Ocean says. “It really saddens me, because I can’t do anything on my side.”

Distance exacerbates this feeling of helplessness. While Ocean has settled in Brooklyn, NY, after completing his undergraduate in Boston, his parents and younger sister and brother still live in a Section 8 apartment across the street from his childhood home in Kalihi, and their financial situation is strained due to the loss of taxi income. Ocean has begun sending a portion of his paycheck each month to support his family. Recently, he bought his younger brother a new futon to sleep on. In September, he’s planning to move out of his Brooklyn apartment and move in with his partner to save money and support his family in Hawaii. “To address these things during this time, you got to make sacrifices, especially if your family is suffering from this, and you come from a low-income Section 8 environment,” Ocean says.

Although he admits that it is difficult to find much positive in a highly politicized world that has weaponized face masks, there have been bright spots to hold on to during this pandemic.

“Being able to work at DEC and come up with programming, sharing stories online through social media, seeing how organizations are transitioning to help communities, seeing big corporations come out and talk about their support for ethnic groups — those things give me hope.”