My mom arrived to the United States in 1983 fleeing from war and genocide to seek refuge. She was 21 years old when she started a new life in Ohio and then set roots in Connecticut, where she raised my older sister and me. Rebuilding her life in this country has led to opportunities never imaginable for my family in Cambodia, but the exposure to pre- and post-migration trauma continues to be felt by entire communities of Southeast Asian Americans (SEAAs).

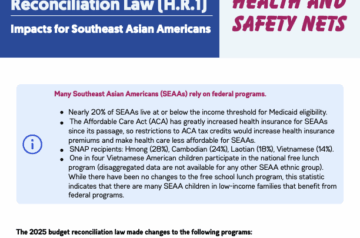

Surviving genocide, long-term exposure to violence, displacement, and anti-immigrant racism in the United States are all factors that contribute to the high prevalence of mental health issues for SEAA refugees. Even decades after resettlement, SEAA communities continue to face high rates of adverse mental health conditions, such as major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders. Continued anti-immigrant racism and oppression perpetuated by the US government through discriminatory policies, from aggregated racial data to systematic deportation, exacerbates the barriers that prevent SEAA communities from thriving. Poor access to culturally and linguistically appropriate health care in this country furthers the severity of these conditions, making the cycles of trauma difficult to break and healing out of reach for many.

I’ve learned that intergenerational trauma has personally impacted me, and through diligent mental healthcare, I’ve worked to heal from painful past experiences. Through a journey of discovering love, empathy, and a compassion for myself and my family history, I’ve learned to dismantle internalized oppression and deconstruct my trauma.

During my first experience working with refugees, I co-facilitated a psycho-social wellness group. We used beauty application as an intervention that aimed to restore trust and build a sense of community for female survivors of torture. Through this experience working with the refugee community, I realized how much it hit home for me to work with clients that had such little trust in others that it was difficult to even have someone apply nail polish on them. As a social worker, I’ve learned that without treating the severe trauma that’s endured by oppressed groups such as SEAA refugees, aspects of poor mental and emotional conditions can be passed onto future generations — this is called intergenerational trauma. The children and grandchildren of refugees can develop attachment issues and isolation as a result of being raised by parents who display psychological distress from experiencing massive group trauma.

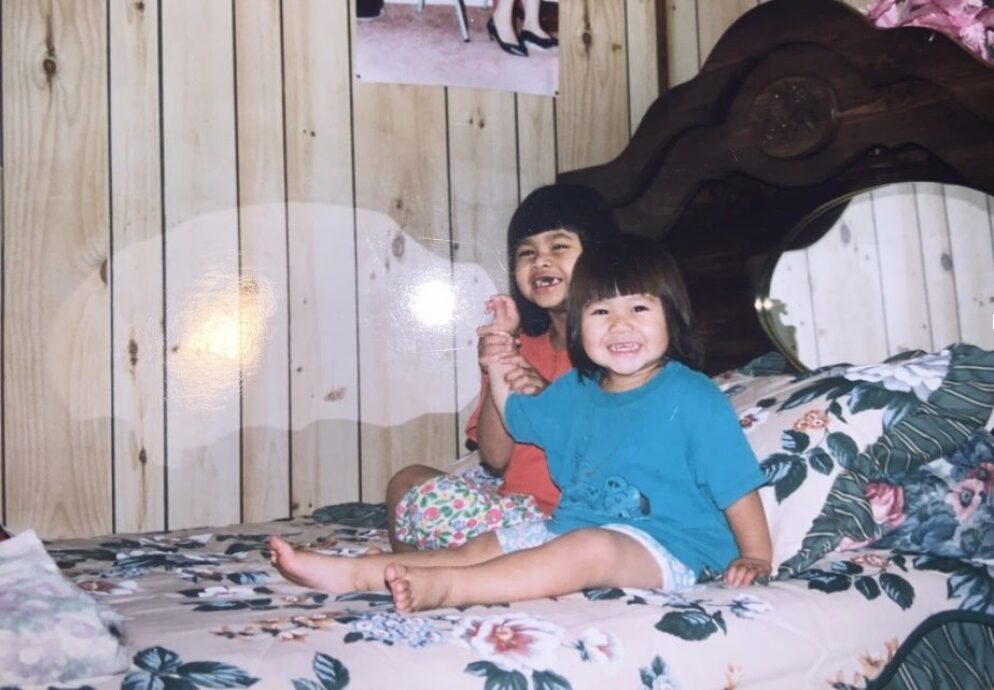

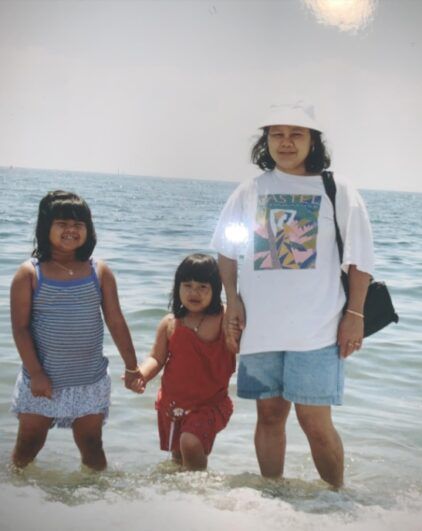

Nary (middle), mom and sister

From a young age I knew that my family was different: we were poor, my dad had uncontrollable anger issues, and my sister exhibited self-injurious behaviors. But because mental health care is highly stigmatized within the SEAA community, it was never talked about and even shamed if brought up. I distinctly recall a time my mom brought my sister to a Buddhist healer because she thought my sister was possessed by demons, when in reality she was struggling with poor mental health conditions. My fight-or-flight response was often activated in my childhood as a reaction to stress. Your sympathetic nervous system is responsible for triggering fight-or-flight responses, where the body may experience a faster heart beat, shortness of breath, and a release of adrenaline into the bloodstream. This is the body’s way of responding to perceived dangers as a mechanism for survival. But chronic activation of this survival mechanism can have lasting impairments to your health. I’ve learned that intergenerational trauma has personally impacted me, and through diligent mental healthcare, I’ve worked to heal from painful past experiences. Through a journey of discovering love, empathy, and a compassion for myself and my family history, I’ve learned to dismantle internalized oppression and deconstruct my trauma.

But my journey to healing wasn’t easy — it was often met with judgement from members of my community, friends, and family. In order for our communities to flourish, we must advocate for policies that promote culturally appropriate and trauma-informed social services, support research of cross disciplinary mental health interventions, and address stigma by normalizing conversations surrounding mental health. Without bringing SEAA voices to the table where policy decisions are made, we cannot advocate for the major mental health needs of our community. We can honor our ancestors and family histories of resilience and strength by showing up for ourselves and the next generation through breaking generational cycles of trauma.

**Pictured at top, Nary (front) and sister

Nary Rath is SEARAC’s Immigration Policy Advocate. To contact Nary, email nary@searac.org.